Michael Ableman is the co-founder and director of a unique urban street farm venture that has grown since its beginnings in 2009 into a thriving multi-farm enterprise employing local residents of the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver.

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is notorious for its poverty and prostitution, for its gritty corners and alleys where drugs and desperation reign. What’s less known is that the community often dubbed “Canada’s poorest postal code” is also home to several verdant urban farms, where leafy greens and juicy tomatoes grow alongside hope and healing.

The single-room-occupancy Astoria Hotel, with its shared toilets and peeling paint, is smack dab in the middle of skid row, hardly a place where you’d expect to find plots full of thriving vegetables. Yet it was on an adjacent concrete lot where Sole Food Street Farms got its start.

Michael Ableman, co-founder of Sole Food Street Farms

Michael Ableman, co-founder of Sole Food Street Farms

Founded by Michael Ableman and Seann Dory in 2009, the organization now operates four farms throughout downtown Vancouver, all on formerly vacant urban land, all run by people who have found themselves living the hard life of the Downtown Eastside.

The pair has discovered that where you can sow the seeds of peppers and radishes, you can also harvest dramatic, positive changes in people’s lives.

Ableman has decades of experience farming in inner cities. Having become a farmer himself at age 18, he went on in the 1980s to found the Center for Urban Agriculture in California, a nonprofit organization that set up farms in some of the United States’ roughest communities.

Over time, that job demanded more of his time in the office instead of in the soil, and so with a desire to get his hands dirty again, he moved to Salt Spring Island on the West Coast with his family about 15 years ago. There, they run Foxglove Farm.

Sowing the Sole seed

Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope at the Urban Frontier

Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope at the Urban Frontier

Several years ago, he got a call that he suspected would change his trajectory again. Members of various social service and nonprofit agencies from the Downtown Eastside wanted to get his insight into their idea of growing fresh food and providing jobs in the downtrodden area.

“I agreed somewhat hesitantly,” Ableman says. “Often one meeting leads to a lifetime of work.

“My focus from the beginning has always been twofold: one is jobs, and the other is the production of quantities of food—two things that I noticed early in my career were missing from most low-income urban areas in North America,” he adds.

“I coupled that with the fact there are thousands of available lots where buildings had been torn down or demolished and thought, why don’t we take this land and grow some food and jobs for neighbours that had neither?”

Ableman, the author of the recently released Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope at the Urban Frontier (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2016), now heads Sole Food solo; Dory moved on a few years ago.

A growing concern

Today, the nonprofit organization produces more than 25 tonnes of fresh produce every year. The food is grown by people who call places like the bedbug-ridden Astoria Hotel home. Many of them are dealing with addiction, mental illness, or both; some face other barriers to employment; all are marginalized.

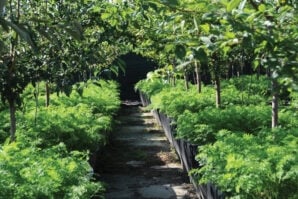

Aside from leafy greens and colourful vegetables, Sole Food Street Farms also grows figs, apples, cherries, pears, quince, and other fruit on 500 trees in a derelict lot turned urban orchard. All of that bounty appears on the menus of more than 30 Vancouver restaurants and can be found for sale at a handful of local farmers’ markets.

It’s the kind of so-called “artisanal” food that more and more chefs and consumers are seeking: seasonal, sustainable, local, and—because it’s as fresh as it gets and not transported thousands of kilometres by truck—delicious.

“When we sell at farmer’s markets, people know that the food they’re buying was grown down the street—not 100 or 1,000 miles away, but literally down the street,” Ableman says.

Urban challenges

From the get-go, Sole Food Street Farms has encountered obstacle after obstacle in terms of getting its operations off the ground. Finding suitable locations is just one of them, with contamination being a major recurring problem.

Contamination

Think of what leaches into the ground from demolished buildings or former gas stations. The founders had to turn down one downtown lot because of the large oil slick that was apparent right on its surface.

After much trial and error, they determined that the most effective type of ground to work on is pavement, because it separates plants from what’s beneath—which, in cities, is almost always soil that’s unsafe for growing food. It also allows easy implementation of the farms’ raised-box, movable systems.

Limited space

Limited lateral space is another challenge in urban settings, and so are increasing land values—with the condo market the way it is in Vancouver, there’s always the chance of eviction due to new construction.

Theft and vandalism

Theft and vandalism are constant threats as well; over the years, $5,000 worth of greenhouse parts have been stolen on a single day, while close to 200 lbs (90 kg) of apples disappeared in a single night.

Uninvited guests

In another instance, a squatter had taken up permanent residence amid one of the farm’s equipment. Then there is damage resulting from rodents: rats like vegetables too, and Sole Food estimates that it loses about $20,000 every year as a result.

Money

The most pressing challenge of all, however, is finances. Ableman says the organization generates about $300,000 in gross annual income from produce it grows and sells, but it needs to raise another $350,000 every year to support its social agenda. As a result, fundraising is as much a part of his job as ensuring his plants are properly nourished.

“I always felt, at the beginning, if we’re going to do this I don’t want to have my hand out forever,” Ableman says. “But I realized after a year or two that, by nature of the social mission and the people we’re employing, we would never ever be able to operate on the same playing field as other farms. I had to accept that because of the social agenda, we would have to continue to raise money.”

Soulful support

Soulful support

Yet for all of the problematic issues that have come up, Sole Food has been buoyed by support, some of it from surprising sources. Vancouver mayor Gregor Robertson has been an advocate, with the farms’ mission fitting in perfectly with his goal to make Vancouver the Greenest City in the world.

Sole Food also gratefully received a boost from Concord Pacific, a powerful developer that believed in its mission and gave the organization access to its largest farming site in the city, now the centre of its operations.

That unlikely collaboration, Ableman says, is what the world needs more of. “We see urban agriculture, when done well, as the ultimate social, political, nutritional, and financial collaboration between municipal government, private and public landowners, foundations and individual funders, and the community of eaters we supply,” he writes in his book.

The project has resulted in measurable benefits. A team from Queen’s University conducted research on the farming enterprise a few years ago and found that for every dollar Sole Food spent on employing the people they do, there was a combined savings of $2.20 in terms of health care, social assistance, prison, and legal system costs.

Then there are the less tangible—but no less significant—effects on the people behind the produce.

Improving people’s lives

The farms and the farming are geared to building a community and bettering the lives of those who cultivate, irrigate, and harvest. The founders trace their mission—to provide rehabilitation through meaningful work—back to the words of Japanese philosopher and natural farmer Masanobu Fukuoka: “The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

“The value in that regard is staggering: we have definitely seen changes in people’s lives that they might not ever have thought possible,” Ableman says. “We have individuals who have been with us for over seven years, and maybe before that they didn’t hold a job for seven months. We have people who were hard-core into their addictions; now one is a supervisor. They’re exceptional.”

Lyle Hayes is one of them. The Prince George native ended up in the Downtown Eastside 40 years ago, at age 18. Heroin lured him there and kept him there. With a father who consumed substances such as Lysol and Listerine before getting sober 11 years before he died, Hayes shattered both his feet after attempting to jump to his death in 2002.

“You wake up out of a coma with your mom holding your hand,” Hayes says. “That was a wake-up call.”

Hayes met Ableman through Dory and helped develop and grow the urban orchard. He continues to work at the farm regularly despite the small doses of heroin he continues to take to keep the jitters away. He says his position at Sole Food is much more than a job.

“It’s a family,” Hayes says. “It’s a nonjudgmental environment. There’s acceptance of who is who; there’s mutual respect.

“I love my job,” he adds. “Tomorrow I’ll be picking the rest of the persimmons and quince. To be in that space is a beautiful thing. I’ll be there at sunset by myself, and it’s amazing. I spend most of my time at the farm.”

The future of food

Ableman doesn’t have any illusions that street farms are the answer to urban food security. However, he does believe we need to do more to reshape our relationship to food.

“We are remarkably disconnected from how food comes to us,” he says. “One of the wonderful things about having a production farm in the middle of the city is that people on a day-to-day basis—on their bicycles, in cars, in trains that pass overhead, or by coming to visit us—can visually, physically see how this all works. That piece is remarkably powerful.

“It’s not just farmers’ responsibility to create a stable food system; it’s the responsibility of everyone who eats. It’s society’s.”

Strengthening your connection to food

Grow your own

If you don’t have space for plots, use containers or window boxes, or lease space in a community gardening allotment. You can also try vertical gardening, a novel—and space-saving—way to grow your own.

Control pests naturally

Create the conditions for dynamic plant health. That means building nutritionally and biologically well-balanced soil and providing stable, consistent growing conditions.

Develop relationships

Get to know your local farmers, learn their stories, and support their efforts.